Fire safety has “stop, drop, and roll.” Bob Pratt wants “flip, float, and follow” to become the

water-safety counterpart.

He knows firsthand the power of such a mantra once it gains traction. In his former career as a firefighter and paramedic, he saw how Fire Prevention Week helped turn basic messages into cultural muscle memory. Kids learned what to do, practiced it, and carried it home. “Stop, drop and roll” became shorthand that saved lives.

But that was just the tip of the iceberg. Now the cofounder and executive director of the Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project (GLSRP), works to develop and promote water-safety education that will help cement such sayings and lessons in children’s minds.

EDUCATIONAL IMPERATIVE

At the center of GLSRP’s vision sits a long-term goal that, in Pratt’s view, is long overdue: a true water-safety curriculum in schools — something that reaches every child the way fire safety once did.

Drowning remains a leading cause of death among young children, and the problem is complex enough

that it can’t be solved by any single intervention.

“It’s a huge problem,” Pratt says. “It’s a complex problem with a complex solution. One way to address it is through public education.”

GLSRP traces its origin to 2010, after co-creator Dave Benjamin experienced a nonfatal surfing incident that sharpened his focus on open-water hazards. Like many grassroots water-safety groups, GLSRP began with public education sessions open to anyone who wanted to attend. However, the organization found its message of water safety left more impact in classrooms. Since then, it has delivered roughly 1,200 to 1,300 school presentations across the Great Lakes region.

The organization tailors its school talks by age, all with a consistent aim: building instincts early and realism later.

For elementary students, the tone stays playful: Pratt uses sea otters floating “holding hands” to reinforce that young kids must stay within arm’s reach of an adult. With older students, the message turns more direct: drowning risk rises when people overestimate their abilities or ignore surrounding

conditions. Rather than preach “don’t,” Pratt frames safety as a continuum: Know your limits, read the environment, and make choices that reduce exposure.

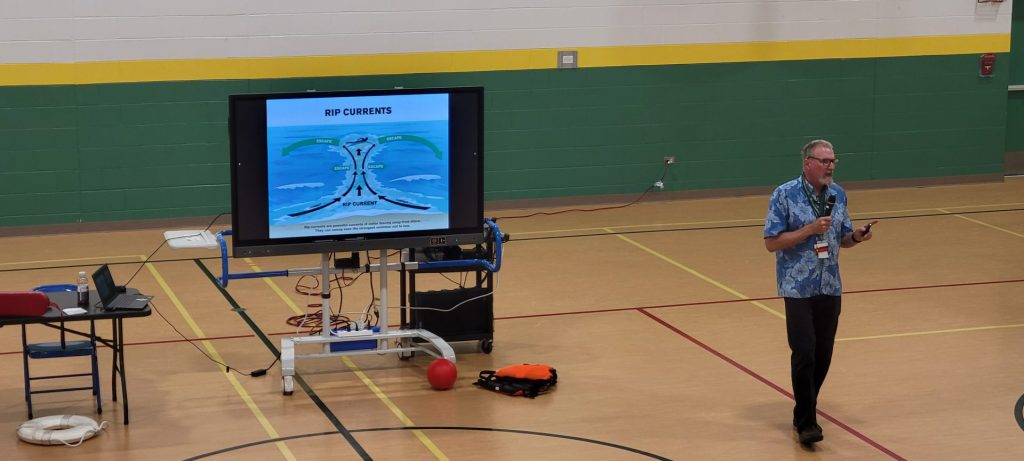

Then there’s the line Pratt wants everyone to remember: “Flip, float, and follow.” Flip to breathe; float to calm down; and follow the current instead of fighting it.

He points to at least one example where the lesson had the intended effect. A student on spring break in Florida got swept into a rip current with her mother. Fortunately, they knew to stay afloat until they were rescued.

AT THE LOCAL LEVEL

GLSRP also fills another gap that Pratt considers foundational and which has gained more attention of late: tracking fatalities. He says there was no single agency consistently tracking Great Lakes drownings. Even when data existed, he says, definitions could be inconsistent. For instance, cases that result in death later may not always be captured and tracked the same way as those causing an

immediate fatality. GLSRP compiles its own numbers using news reports and other public information.

It now lists 1,417 Great Lakes drownings since 2010.

That data fuels GLSRP’s broader push for policy and school-based education across the Great Lakes states. The group has worked with partners to support water-safety legislation in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and beyond, covering issues ranging from shoreline rescue equipment to education requirements.

The group has long provided a living example of the approach now called for by the U.S. National Water Safety Action Plan. In developing the 10-year roadmap to coordinate drowning prevention strategies nationally, that nation plan’s originators came to the conclusion that no one-size-fits-all solution exists, but that such plans will prove most successful when states adapt them to address local risks and realities.

For Pratt, it all ties back to the same premise: Drowning prevention should be normalized and as relentlessly taught as fire safety.

“We’re making a lot of effort highlighting what a problem it is and hopefully starting to address it more,” he says.