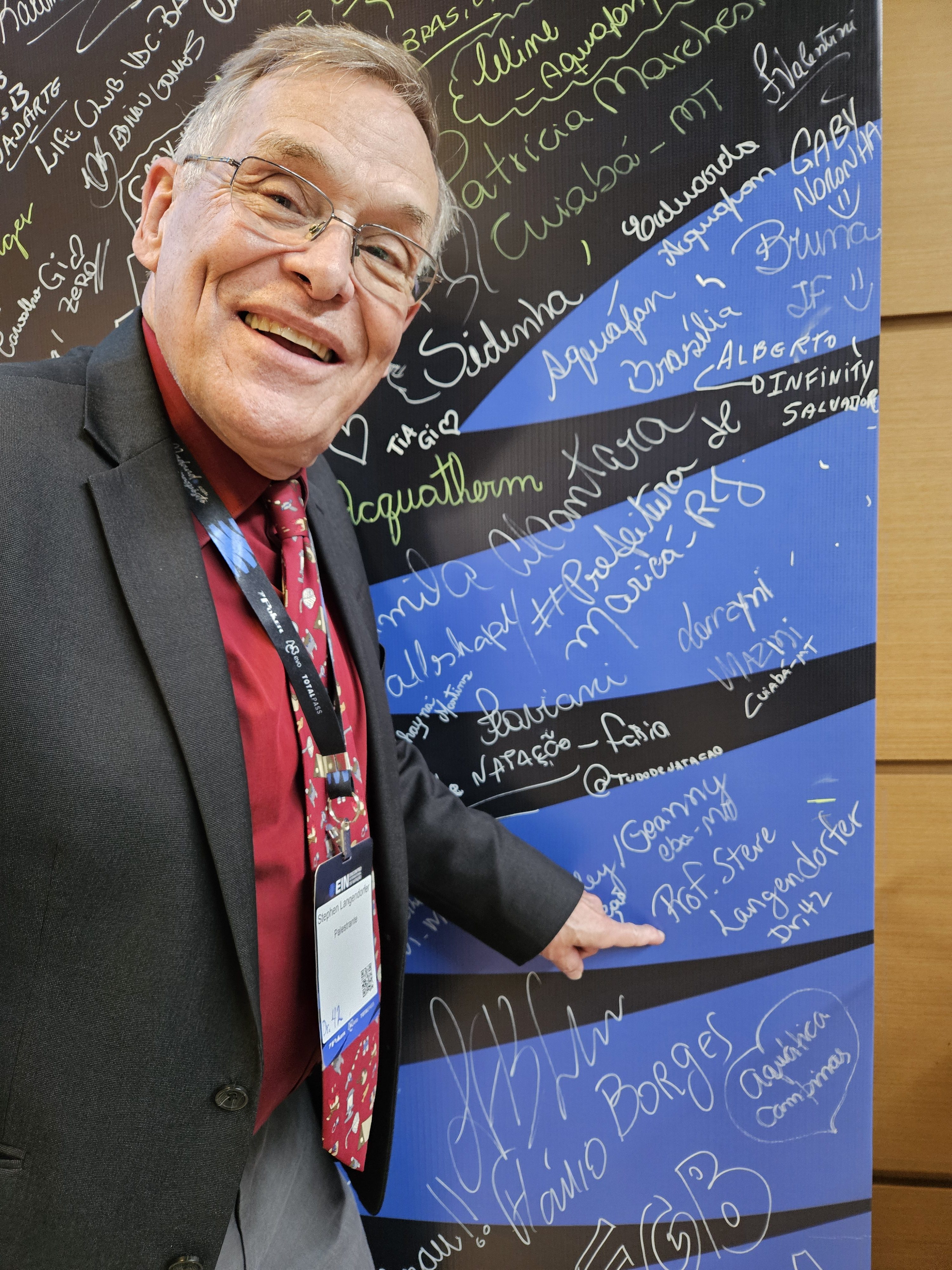

When you think about the movement toward science and data in developing codes, standards, programs and best practices related to aquatics, you can thank Stephen J. Langendorfer, Ph.D.

The professor emeritus at Bowling Green State University in Ohio belongs to an elite group of individuals who worked behind the scenes to introduce science into aquatics well before the call for it.

For more than 50 years, he has volunteered for the American Red Cross, with much of his work on the Scientific Advisory Council. This group reviews Red Cross programs against the available scientific evidence, making sure they align. There, he currently holds the position of vice chair of the Aquatic Sub-council.

By merging his studies of motor development with his love of swimming and aquatics, he has helped forward the understanding of how drownings occur and how people learn to swim.

POOLSIDE ACADEMIC

A recognized authority in the areas of lifespan motor development, aquatics and drowning prevention, Langendorfer earned degrees from SUNY-Cortland, Purdue University, and University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Channeling his knowledge toward swimming, aquatics and drowning prevention made complete sense. “It goes all the way back to my childhood,” he says. “One of our family activities was always trying to find a swimming hole or doing something around the water. In fact, the humorous Family Rule No. 1 is, ‘Never go anyplace without a swimsuit.’”

But, in university, when he decided to apply his understanding of movement to swimming and aquatics, not everybody shared his enthusiasm.

“Both my major professors [during my doctoral studies] said, ‘You have to give up this silly aquatics stuff,” Langendorfer recalls.

Their reason? They didn’t believe that aquatics as a field placed much stock in research, data or academia in general.

Langendorfer agreed with that statement. But, as he saw it, that only proved the existence of a gap that needed to be filled. Plus, his studies about lifespan motor development seemed to correlate with swimming.

“All the stuff I was studying was very applicable to what’s going on in the water with kids,” he says. “They can start learning to swim at about the same time as children learn to walk and then hop and skip and run and jump. It’s a very parallel process.”

ELEVATING THE FIELD

Early in his career, Langendorfer was faced with the lack of science in aquatics.

“When I first was helping the Red Cross do some revisions back in the 1980s, I remember the group of us, who had some expertise, would sit around the coffee table and say, ‘Well, this is how we should do it, don’t you think?’” he remembers. “Every time that happened, I’m thinking, ‘That’s not the way we should be deciding this.’”

Toward that end, he has authored more than 200 scholarly and applied publications. This includes the book “Aquatic Readiness: Developing Water Competence in Young Children,” published in 1994, which pioneered the concept of water competence.

It also promotes a teaching approach that he learned about in his graduate studies. Called a “learner-centered approach” or “indirect teaching,” it counters the more common “teacher-centered teaching,” or “the command style,” where the instructor demonstrates movement for the students, who then mimic the motion.

“The notion is that learners construct their own learning,” he explains. “The job, then, of the instructor or coach is to facilitate that learning process.”

To facilitate the sharing of research, Langendorfer was the founding editor of the International Journal for Aquatic Research and Education. In the last decade or so, it has published articles from around the globe, with downloads reaching a half million recently.

“Every country is embracing the need to study the science of swimming,” Langendorfer says.

CONTINUING WORK

His work with the Red Cross’ Scientific Advisory Council continues to this day. It currently is trying to determine the optimal water temperature or combination of air and water temperature for people of all ages in the pool. This involves finding and reviewing the available research in this area.

It also works with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which provides Red Cross with grants to perform original research on drowning and drowning prevention. Of special interest: Why certain minority groups see higher drowning rates than the general populace and what can be done to lower these rates.

Fortunately, the work of Langendorfer and people like him has paid off. “There’s a pretty good evidence base that has built over the past decade that, in fact, learning to swim is one of the most important drowning-prevention strategies,” he says.