A bill aims to curtail so-called “drive-by lawsuits” against facilities that do not comply with the Americans for Disabilities Act.

House Resolution 620, titled “The ADA Education and Reform Act of 2017,” would essentially delay an individual’s ability to immediately file a lawsuit. Aggrieved parties would have to issue written notice to property owners or managers specifying the barriers that prevent them from accessing a public accommodation. Operators then would have 60 days to comply.

Sponsored by Rep. Ted Poe (R-Tex.), the legislation passed the House and has moved to the Senate.

This “notice and cure” approach is intended to reduce the number of predatory lawsuits sprung on businesses and building owners accused of falling short of the numerous ADA requirements that regulate architectural elements, such as parking lots, bathrooms and wheelchair ramps.

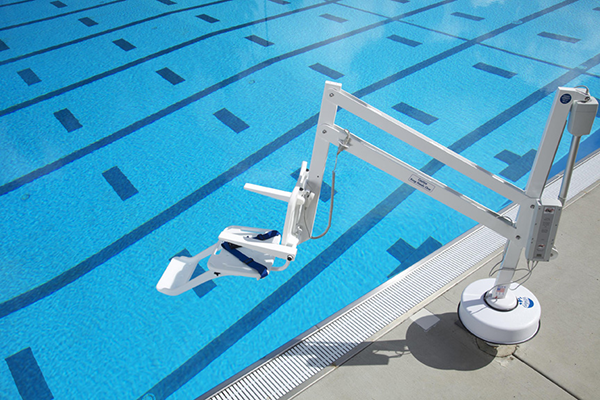

HR 620 has special significance to the aquatics industry. In 2010, the Department of Justice, which oversees the ADA, enacted a law requiring commercial pools and spas to have a disability-access lift. Operators had until early 2013 to comply. Numerous hotels with swimming pools that had not installed a pool lift by that deadline were sued.

“The good news is that we’ve seen a sharp decline in the number of pool-lift lawsuits,” the vast majority of which were brought forth by one attorney, said David Raizman, an office managing shareholder at Ogletree Deakins, a firm specializing in ADA compliance.

Raizman has defended several facilities in access-related lawsuits.

But there remain multiple areas where a facility could be found guilty of not meeting the full requirements of the law, Raizman said. As it is written, HR 620 will not provide an adequate safeguard in some instances, he said. Some facilities have legitimate reasons for not installing a pool lift, he contends. For example, pools built before the law went into effect might not have the physical space to accommodate a lift. Such facilities are still vulnerable to lawsuits.

“Structurally, the problem with the Poe bill is that it does not give those with a defense a real chance to have that matter decided by a court without great [legal] expense,” Raizman said.

Nor does the bill address the issue of damage awards, he said. Under the ADA, an individual who is successful in getting a barrier removed by court order is only eligible to receive compensation for attorney’s fees, not damages. At least that’s how it works in most states. California, Texas, New Jersey and New York will award damages in non-compliance cases.

Critics of HR 620 also say it undermines the overall intent of the ADA by prohibiting people with disabilities to expedite the removal of a barrier through legal enforcement.

“Without this critical enforcement mechanism, compliance under the ADA will suffer and people with disabilities will be denied the access to which they are entitled under the law,” the ACLU says in a multi-point argument against the bill.

Champions of the bill, however, say it’s a step in the right direction, one that could give well-meaning business owners legal protections to make structural changes first without being slapped with a lawsuit.

“We’re monitoring it,” said Jennifer Hatfield, APSP government affairs director. “APSP supports the overall intent of the legislation.”