Scene from the television show “Baywatch”:A man and woman embrace on the edge of a cliff above crashing surf. Suddenly, the man slips and falls into the water. He quickly begins to panic thrashing his arms and yelling “Save me! I don’t want to die!” A lifeguard appears and dives off of the cliff just as the man disappears underwater. Moments later, the guard surfaces with the unconscious victim in tow. He reaches shore, and surrounded by an admiring crowd, begins CPR, yelling, “Wake up! I’m not going to let you die!” Moments later the victim begins to cough. He opens his eyes and miraculously, he is OK. As the crowd cheers, the victim looks up and shakes the lifeguard hero’s hand, thanking him for saving his life.

I’ve spent much of my career watching scenes like the one depicted above where a drowning victim acts and appears in a way that’s nothing like real life.

In 2011, a study by Stathis Avramidis identified and analyzed 780 drowning scenes in film and television. In more than 200 cases, the event was inaccurately represented. Most scenes featured a panicked victim and several portrayed people floating motionless, face down on the surface with their arms extended. One of my favorites appears in the movie “The Sandlot,” where a character pretends to drown so that the pretty lifeguard will “save” him using mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

Over time, I began to wonder if these false portrayals from the entertainment industry could actually influence how people think about drowning. So, beginning in 2010, I spent three years surveying a group of randomly selected adults using the scene from “Baywatch” described earlier as a sort of test. The results were discouraging.

All too often the media, especially the film industry, create and perpetuate myths about drowning that influence the public’s capacity to recognize fatal submersions while they’re in progress. Even among lifeguards, especially younger, more inexperienced ones, these dramatizations may impact their ability to identify and quickly respond to a drowning victim. Hollywood drownings also feature scenes in which the victim is resuscitated after a few quick mouth-to-mouth breaths, which in reality never happens.

This study suggests a real need for educational programs that focus on dispelling myths about drowning. This will dramatically reduce the number of fatalities, especially among children.

Tallying the numbers

The description of the scene from “Baywatch” was given to 406 respondents along with a seven-question survey. A total of 59 percent indicated that this represented either an “accurate” or “fairly accurate” portrayal of drowning.

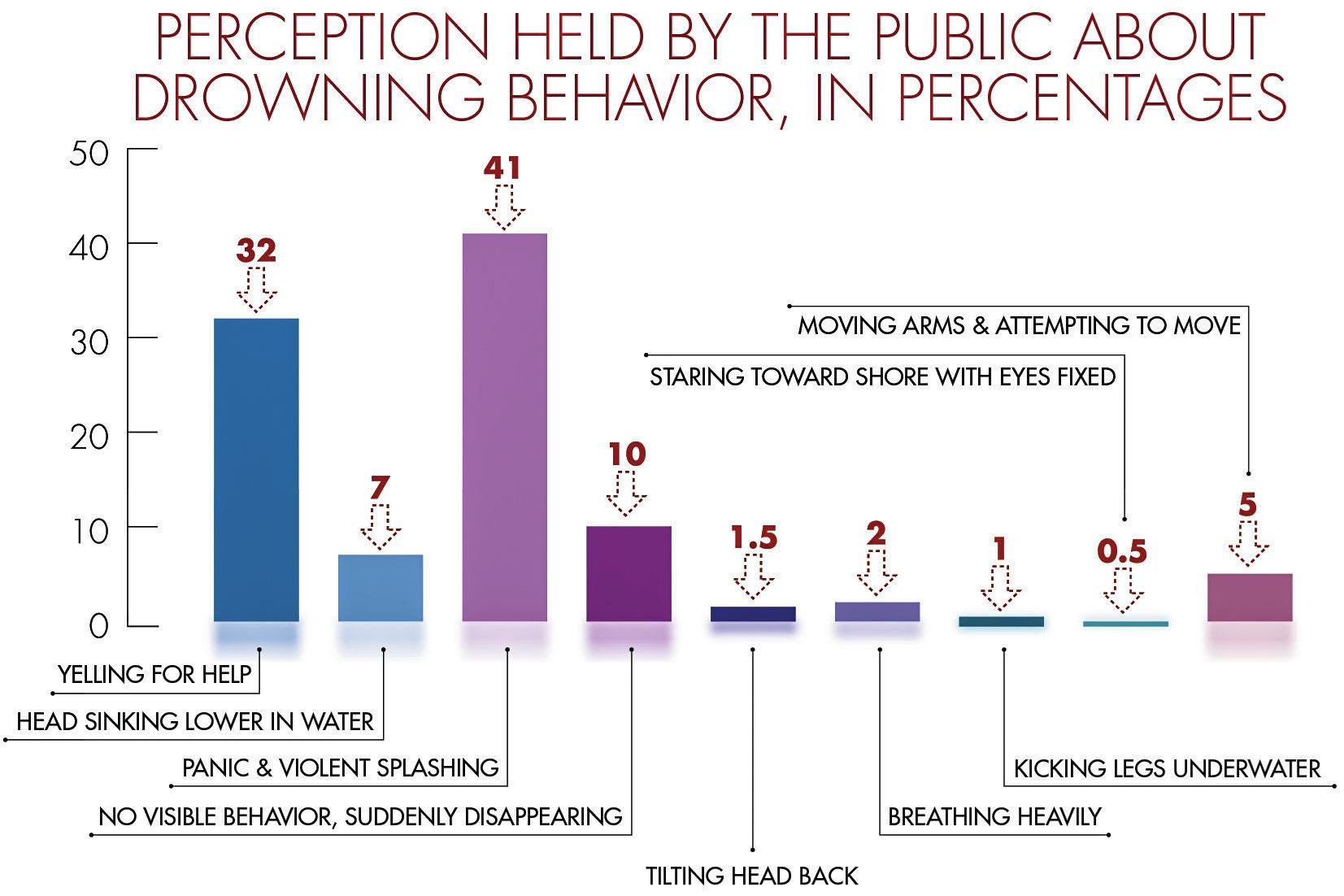

The respondents also were shown a list of behaviors and asked to identify which ones most realistically represented a drowning. Most of the behaviors given were ones commonly dramatized in movies and television, but do not actually occur in active drowning episodes.

Sadly, only 13 percent of the respondents were able to select the correct behaviors.

Most people believe that victims panic violently at the surface of the water and usually yell for help before becoming submerged. Indeed, in this study, about two-thirds of the respondents stated that they held those two beliefs about drowning.

A number of respondents had some sort of lifeguard training in their backgrounds, and this subset contained significantly more accurate responses than those without training. Still, 32 percent of the respondents with formal lifeguard education were unable to accurately identify behaviors associated with drowning. Instead, a significant number of these subjects believe that “panic” and “yelling for help” represent two valid drowning indicators.

Almost all of the lifeguard respondents knew that it is not possible to bring a victim back from clinical death by CPR alone. Most respondents without lifeguard training were not aware of this.

One survey question asked subjects if they were able to recall specific movie scenes or TV episodes depicting someone drowning. All of the respondents stated that they were able to remember, in detail, several drowning scenes from movies and/or television.

The sad truth

Here’s the reality that belies the Hollywood myth: As actual drowning victims begin to hyperventilate, their heads drop lower and lower in the water. They rarely yell for help because physiologically their respiratory system is designed for breathing. Speech is secondary. Consequently, breathing must be fulfilled before it is possible for them to speak or yell for help.

During an active drowning episode, victims usually don’t wave for help as Hollywood would have us think. Instead, the natural response is to extend the arms laterally, often pressing them down onto the surface of the water to create leverage. This is commonly known as the first stage of a drowning episode and typically varies from 30 seconds to four minutes or more. It is not uncommon for a victim to submerge and resurface several times before going under permanently.

As part of my government contract work, I have studied more 1,000 drownings and several thousand near-drownings. Some of these incidents were captured on surveillance video, and I have witnessed a significant number of fatalities involving young victims who were actively drowning within the unobstructed view of an adult. Yet the adult never responded. Presumably, this was because the victim’s behavior didn’t correspond with a stereotypical — and erroneous — concept of drowning.

During a tragedy at a hotel pool involving a 6-year-old girl that was captured on surveillance video, I observed 44 adults passing by, or remaining in, the vicinity of the victim during the four-minute drowning episode. None of the adults realized the child was drowning.

In another case involving a 12-year-old girl, also captured on video, six adults were within 20 feet of the victim. The girl surfaced, submerged and resurfaced three times before finally settling to the bottom of the water in the shallow end.

The Drowning Prevention Foundation reports that 19 percent of drowning deaths involving children occur in public pools with certified lifeguards present. At a pool in South Carolina a 4-year-old boy drowned while two lifeguards were on duty. In a statement from one of the lifeguards, he insisted that the boy was playing and not in distress. It was only after a bystander observed the child on the bottom of the pool that the lifeguard noticed something was wrong. By then, it was too late for resuscitation.

In an incident involving a teenage boy swimming at a beach in Cape Cod, there were two lifeguards stationed directly in front of the victim, less than 100 feet away, but each failed to recognize that a drowning was occurring.

Next steps

The study suggests the need for educational programs that focus on dispelling myths about drowning. The media’s popularized, highly fictional portrayals can create false perceptions that may be responsible for contributing to the drowning rate, especially among children. It is critically important for members of the public to have accurate knowledge about drowning so they can respond quickly in an emergency. A better understanding will dramatically reduce the number of fatalities.

This study also highlights a need for better drowning recognition training among water professionals. Clearly, organizations responsible for certifying lifeguards must place more emphasis on how to identify a drowning victim. Videos depicting real-life episodes should be utilized in training curriculum for lifeguards. It’s also important to provide regular, ongoing training featuring re-enactments that imitate real drowning behavior rather than the behaviors often portrayed in the movies.

Perhaps writers and directors in film and television can be persuaded of the importance of accurately portraying drowning. Organizations such as the American Red Cross, the YMCA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention must continue to promote and educate the public about the importance of “touch” supervision. And everyone who comes into contact with a body of water, whether it’s the ocean or a swimming pool, must be made to realize that the concept of “drownproofing” is not valid.