One of the newest trends in recreational water is the opening of surf parks. With the first in the US opening in 2016, it seems that more artificial surfing lagoons are popping up everyday. A dozen new facilities are already planned around the world in the next few years. As these venues increase in popularity, we would expect an increased exposure to recreational water illnesses (RWIs) at these facilities.

A recent fatality bore out this concern.

While some argue that surf parks do not require the kind of sanitization methods used on other aquatic bodies, I believe it is crucial.

Fatal threat

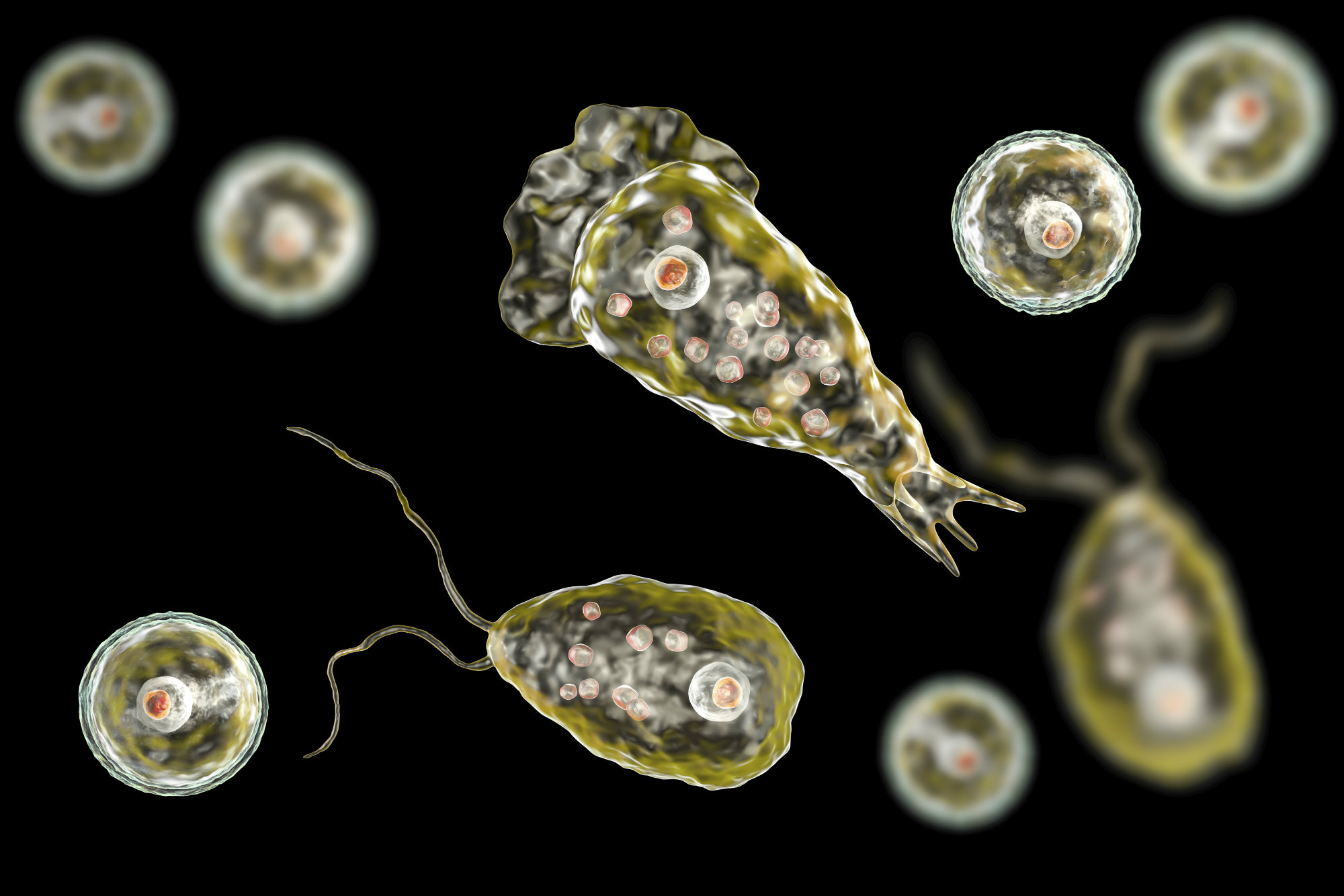

One area of concern specific to these venues is the threat of being exposed to Naegleria fowleri, a free-living amoeba that causes primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) when it enters a person’s nasal cavity. Known as the brain-eating amoeba, it thrives in warm, fresh water. The CDC recorded 145 infections from 1962 to 2018. Almost all were fatal, with only four survivors. Most are found in southern states where the water temperature is naturally higher, with about half of reported cases coming from Florida and Texas.

While the first wave pools were built in the U.S. in the late 1960s, surf parks offer a different experience. These man-made lagoons utilize a mechanical “wave foil” or a series of air chambers to create large ridable waves, more similar to those found in the ocean. Surfers rave about the custom wave settings. Similar in size to surf parks are cable parks, which use electrically driven cables to tow skiers or wake boarders.

Most surf parks include one main body of water that offers several surf areas with a variety of wave styles appropriate for different abilities. The goal is to create a surfing or watersport resort without the need to go to a lake or ocean.

One of the largest inland watersports facilities is the BSR Cable Park and Resort in Texas, with both cable park and surf resort amenities. BSR also advertises America’s longest lazy river, and a large slide tower/plunge pool called the Royal Flush.

During the 2018 season, a 29-year-old New Jersey man was diagnosed with a fatal infection from the Naegleria fowleri amoeba. Authorities believe the man was likely exposed to the amoeba while surfing at BSR.

Treatment questions

From a general standpoint, these surf and cable park facilities should be treated just like a pool, waterpark, or any other recreational water venue, taking into account specific parameters based on their size and use.

Some developers argue that these facilities are so much larger than pools or waterparks that swimming pool codes and standards don’t apply. Others contend that riders are not in the water, but rather on a board of some sort, so water treatment doesn’t matter. Over the past few years, many of these man-made venues have opened without proper water filtration or disinfection.

But being larger doesn’t reduce risks associated with untreated water. And the characterization of that amount of water as “untreatable” just isn’t accurate. Some of the largest man-made lagoons are up to 1 million square feet, or 20-plus acres. Depending on the depth, this could equate to 50 million gallons of water, compared to the average of 750,000 to 1 million gallons in an Olympic-size pool. However, a typical municipal drinking water system may treat more than 200 million gallons per day, with systems very similar to those used for pools and waterparks. So the systems and equipment are available.

Some developers have raised concerns that moving this much water through the piping system could create safety risks due to high water velocity. This is not the case. The water velocity through main drains and inlets can be controlled by designing the appropriate number, size and location in accordance with the system flow rate. Consider a spa or hot tub as an example. A spa is a small body of water with a very high turnover rate requirement due to the nature of use. But they have minimal surface area to locate suction outlets, so manufacturers designed covers to reduce the water velocity to safe and acceptable rates. The same principles are applied to larger pools, which require higher flow rates. These design considerations are scalable even for extremely large recreational water venues such as surf pools. Certainly, more and larger suction outlets would be required to accommodate the higher flow rates, but prudent design would limit the suction velocities to appropriate levels.

The distinction between riders being “on the water” instead of “in the water” doesn’t negate the need for water treatment. Consider the flow-boarding machines that have been popular at waterparks for many years. Manufacturers know most riders will fall, so they surround the ride with padding and other safety devices. Similarly, surf parks should know riders have a risk of falling in the water and should plan accordingly. While great surfers may be able to ride a wave and exit with dignity, my experience surfing always left me face first in the water. It is expected that most surf park riders will at some point fall into the water and risk exposure to any RWIs present. I see this type of exposure as an increased risk for things such as Naegleria fowleri due to the higher likelihood of water forcefully entering the nose when a surfer falls or is submerged by waves.

Appropriate standards

Another question is what water-treatment standard these facilities should follow.

Some claim that a standard doesn’t exist for these facilities. However, the first edition of the Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC) was published in 2014, before these facilities were open. It defines an aquatic venue as an artificially constructed structure or modified natural structure where the general public is exposed to water intended for recreational or therapeutic purpose and where the primary intended use is not watering livestock, irrigation, water storage, fishing, or habitat for aquatic life.

Cable parks and surf parks meet this definition and should follow MAHC standards, just like any aquatics venue that exposes users to recreational water. This means these parks must filter the water and maintain a minimum of 1ppm of free available chlorine for sanitation purposes whenever the facility is in use.

Specific to Texas aquatics venues, a 2017 update to the state’s Health and Safety Code was made to include “artificial swimming lagoons.” The update was meant to address the larger nature of such facilities. Section 341.064 defines an artificial swimming lagoon as “an artificial body of water used for recreational purposes with more than 20,000 square feet of surface area, an artificial liner, and a method of disinfectant.” The code requires owners, managers and operators to maintain artificial swimming lagoons in a sanitary condition, maintaining a minimum free-chlorine residual of 1.0 ppm, or other approved disinfection parameter. While these regulations and practices have been a normal part of daily operations in municipal pools, private waterparks and resorts for decades, it appears some cable and surf park operators don’t understand the importance of these basic principles.

When BSR first opened, it was reported that the resort used a biocide and a blue dye in the water but not standard sanitation or filtration. Following last year’s fatality, the CDC inspected the park and found little to no chlorine and high turbidity. The report stated “[a] free chlorine residual was not detectable.” The CDC inspection also stated there was “no routine chemical treatment, monitoring, scrubbing of wetted venue surfaces, filtering, or record keeping” at the facility. These results have more in common with an untreated natural body of water than a recreational venue.

After the incident in Waco, BSR’s owners hired a water-quality expert to design a new water-treatment system. The park has invested in a new mechanical treatment system, including filters that can remove particulate to less than 5 microns, along with a disinfection system that can maintain a minimum of 1 ppm of free available chlorine. Additionally, BSR upgrades include an ozonator as a secondary sanitation.

When it first opened, this park appeared to be a high-risk venue due to the lack of water treatment. With these new improvements, it now appears to be setting an example for similar venues.