When the ownership behind 10 CoCo Key Water Resorts auctioned the properties off in 2011 for bargain prices, the news startled employees and industry members alike.

“It wasn’t something you could see at the property or that we were privy to,” recalls Rachel Klekman, who was handling marketing for a handful of CoCo Key properties in the Northeast. Now Klekman is director of marketing at Willner Realty and Development Co., a commercial real estate firm in Ardmore, Pa., that bought two CoCo Key assets through the auction.

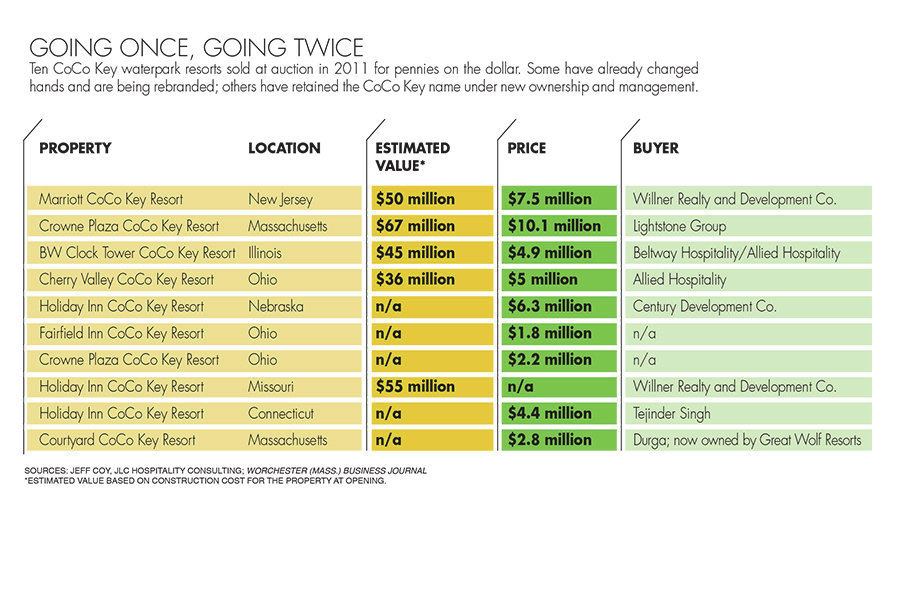

Others agree. “The sale happened very suddenly,” says Jeff Coy, an industry consultant and president of JLC Hospitality Consulting in Cave Creek, Ariz. “They sold for 50 cents or less on the dollar.”

Some wondered whether the sale was a sign that the fast-growing waterpark industry was about to hit choppy waters.

However, two years later, the fire sale of those CoCo Key properties looks less like a cause for panic about the future of waterparks than an unexpected opportunity for real estate firms interested in picking up properties with a lot of room for financial growth.

That surely was the case for the Lightstone Group, a New York-based real estate firm that made a successful bid for the CoCo Key located outside of Boston.

“We weren’t looking to get into the waterpark business,” explains Joseph Teichman, executive vice president and general counsel at Lightstone, which owns 14 hospitality properties and is actively growing its holdings. “We believe in the waterpark business, but we approached this as a hotel asset which also had a waterpark. … [The previous owners] led only with the waterpark and didn’t address the rest of the hotel needs.”

Lightstone bought its Danvers, Mass., CoCo Key for approximately $10 million, a fraction of the $67 million that it reportedly cost to build the property in 2007, according to JLC Hospitality’s 2011 Construction Report North America.

(Even Great Wolf, which was not one of the original auction purchasers, couldn’t resist such bargains. The waterpark resort giant appears to have snapped up a CoCo Key property in Fitchburg, Mass., with the intent of transforming it into the first Great Wolf Lodge in New England.)

But the original owners’ losses may ultimately prove to be the industry’s gain. As Lightstone, Willner and others make changes at their CoCo Key properties, their decisions offer insights into operational areas that were overlooked even by a high-profile national brand such as CoCo Key.

CoCo Key history

While Great Wolf and Kalahari were founded in 1997 and 2000, respectively, CoCo Key Water Resorts emerged at the height of the real estate boom in 2006 through the efforts of Wisconsin-based Wave Development, Sage Hospitality of Denver, and others.

In contrast to Great Wolf or Kalahari, which offer elaborate, all-encompassing waterpark resort experiences for hotel guests only, CoCo Key was designed as a more flexible and more modestly priced alternative to those powerhouses. Guests could stay at the hotel, visit the waterpark for the day as a family outing, or combine the two.

There were other differences, too. While Great Wolf and Kalahari typically build new parks from scratch, the developers of CoCo Key instead turned to underperforming hotels, renovating them extensively and repositioning them as waterpark resorts.

To some degree, the approach worked, drawing guests to the rebranded CoCo Key properties. Even now, as a variety of new owners have taken over the different locations since the 2011 auctions, several have chosen to keep the CoCo Key name.

“Despite the challenges, CoCo Key was a brand that we were able to maintain as an affordable product that wasn’t too far away,” says Klekman of Willner, which bought two assets, one in Mount Laurel, N.J., and one in Kansas City, Mo. “Both had very aggressively marketed [themselves] in their areas, and it has become a recognizable brand, even 60 miles to 80 miles away from the property.”

“That tells you how important that brand is, for the CoCo Key name to stay intact across markets,” observes Ted Watson, vice president of Orlando, Fla.-based CNL Financial Group, which has owned the Orlando CoCo Key Water Resort since 2008. (The property, which is also still managed by Sage, was never put up for auction; it was not part of that portfolio.) “It was really just the background change in ownership going on [with the properties sold in 2011], not a problem with the brand.”

What led to that ownership change? It is unclear. Sage, which managed many of the CoCo Key properties and helped develop the concept, declined to discuss the reasons.

Many suspect the economy was a factor. “The hotel with an indoor waterpark is a great concept,” Coy says. “The reason this stalled out was the recession, which lasted longer than anyone thought it would.”

Under new management

Two years and millions of dollars later, the new owners are rolling out the latest versions of their CoCo Key acquisitions.

“We put $15 million into this asset after we acquired it,” Teichman says of the Crowne Plaza Coco Key Resort in suburban Boston, now known as DoubleTree by Hilton. “It will deliver a very good DoubleTree experience.”

Where did that money go? Not to the waterpark, which just opened in 2007. “The waterpark didn’t need a whole lot of capital,” Teichman says. “We thought there were other ways to increase guest satisfaction.”

In Missouri and New Jersey, Willner executives reached similar conclusions about their properties. “The water resorts were fairly new,” says Klekman, while the hotels definitely were not. So the company chose to upgrade guest rooms, revamp HVAC systems, modernize the elevators and make other improvements. “If something was broken, they said, ‘Let’s get it fixed,’ ” Klekman recalls. “It was nice to have such hands-on management.”

In Massachusetts, Lightstone began its renovation work by looking at the hotel’s guests and decided to position the property to serve three core types: families visiting the waterpark, business travelers and meeting room guests at the hotel for a conference or a wedding. “We believe in the waterpark facility — it’s profitable,” Teichman says. “But we also believe in running a full-service hotel.”

With that in mind, Lightstone reconfigured floors to create 60 suites for families and two executive floors with a corporate lounge. The check-in area was divided into separate spaces for hotel guests and waterpark visitors, extending the waterpark theme into the family-friendly spot while keeping a more buttoned-up appearance for business travelers. And new retail was added, from a kiosk for preteen guests to Starbucks for all the sleep-deprived parents and corporate road warriors.

These changes suggest just what might have been missing under the previous ownership at CoCo Key and perhaps other waterpark hotels as well: lack of attention to hospitality operations, compared with the waterpark attractions.

“A waterpark hotel really acts and thinks like a hotel,” CNL’s Watson says. “You have got to understand the fundamentals of revenue management and operating a hotel.” n