It’s all about the reps — drill repetitions that is, how many repetitions a trainer can provide to a lifeguard or a lifeguard team during in-service training.

Repetition of drills builds skill proficiency and rescue readiness, leading to your rescuers’ tactile skill proficiency and readiness to become automatic.

In past articles, I’ve focused on automaticity and unconscious competence, and how they apply to in-service training. When rescuers can automatically perform their rescue duties at a high level quickly, it allows them to have an expanded view of an incident, allowing for better adaptation to unforeseen challenges that will manifest during the emergency.

The trainer’s goal should be to maximize opportunities for rescuers to physically train by cutting out any excessive waste of time in the training process. So, let’s review how to build a successful 30-minute in-service training with more repetitions.

THREE-MINUTE SOLUTION

Multiple drill opportunities allow the rescuers to make mistakes and quickly correct those mistakes. It also allows them to improvise and figure out more efficient ways to meet the skill objective, work as a team, and improve their communication within the rescue team. As the trainer, communicate the objective with the time limits, and provide the environment for the rescuers to build proficiency and team cohesion.

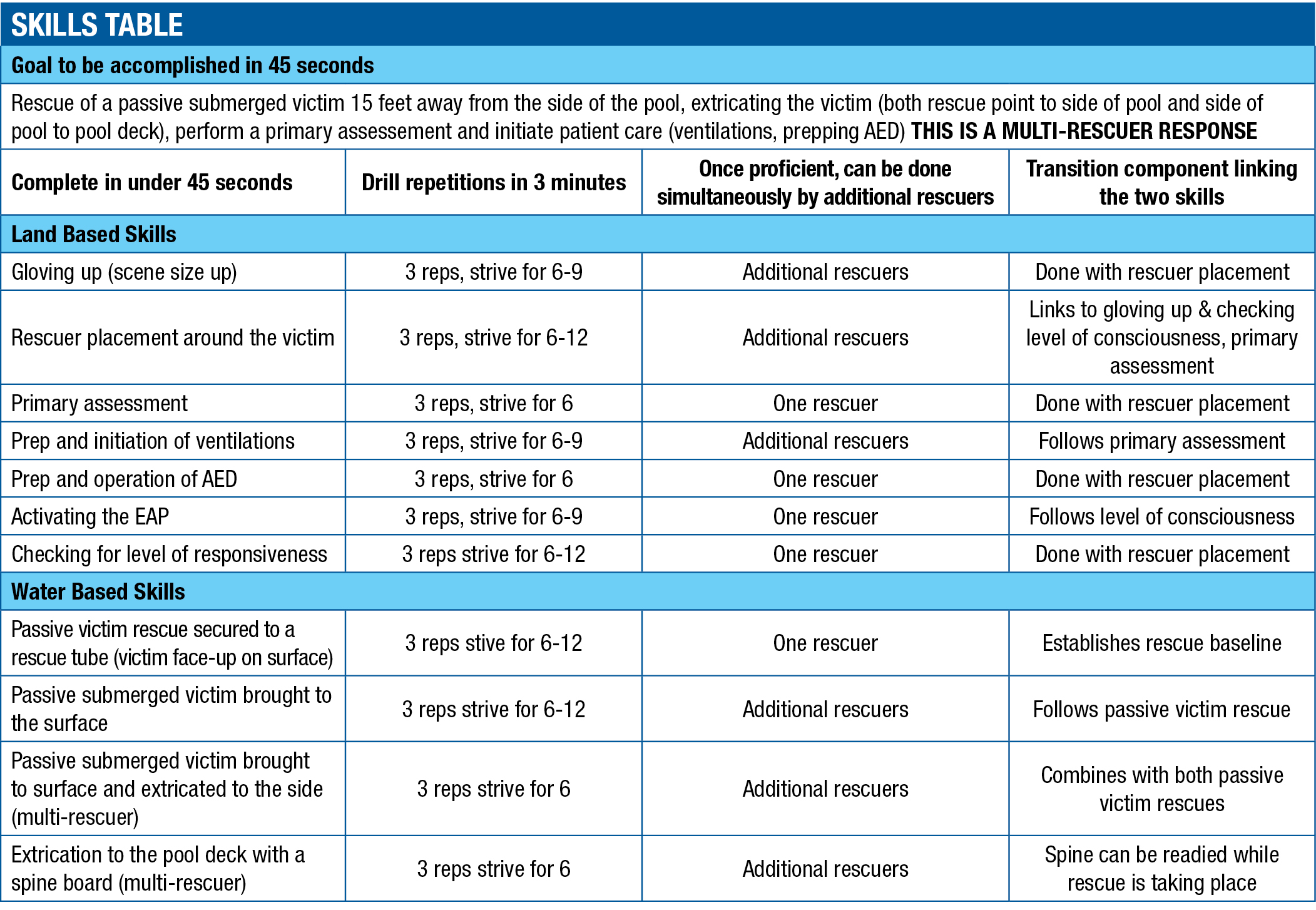

I apply a skill table model to manage time needed for each skill and the transition to another skill. The skill table is built around the goal, “Three drill repetitions in three minutes.” The number of drill repetition considers depth of water and reset time between drill repetitions. The number three is the baseline number, meaning that if you can easily accomplish three drill repetitions in three minutes, then you should attempt to double or triple the number of drill repetitions.

Three minutes is just enough time to keep the rescuers engaged, either actively or passively. If they are not currently doing the drill, we want them watching, prepping, staging and developing efficiencies in anticipation of their turn. Three minutes encourages the staging rescuers not to lose focus on the objective. REMEMBER: Not every drill needs to have every rescuer doing the drill.

Consider this: In three minutes, a passive submerged victim can be rescued, extricated to the deck, and provided patient care including ventilations with a BVM, use of an AED, and 5 cycles of CPR.

From a trainer perspective, managing time and skill proficiency is a goal for in-service. If a trainer can’t achieve three drill repetitions within the time limit, then they should review what’s slowing down their effectiveness:

· The skill was too big, and should have been initially broken down into smaller pieces;

· Too much time explaining the objective(s) of the drill;

· The training area was too big, meaning rescuers were spending more time going from Point A to Point B than on doing the drill repetition;

· The time for reset took too long, due either to refurbishing the equipment, getting rescuers back into starting positions, or allowing the rescuers to be distracted in between drill repetitions;

· The ratio of rescuers to instructors is too high, and effective instruction gets lost in the noise.

Why use a 3-minute block? It’s small, compact and a lot can be done. If the trainer identifies a specific step that rescuers are frequently neglecting (example: correct finger placement when checking for a carotid pulse while maintaining an open airway), the trainer can dedicate a 3-minute block on pulse check.

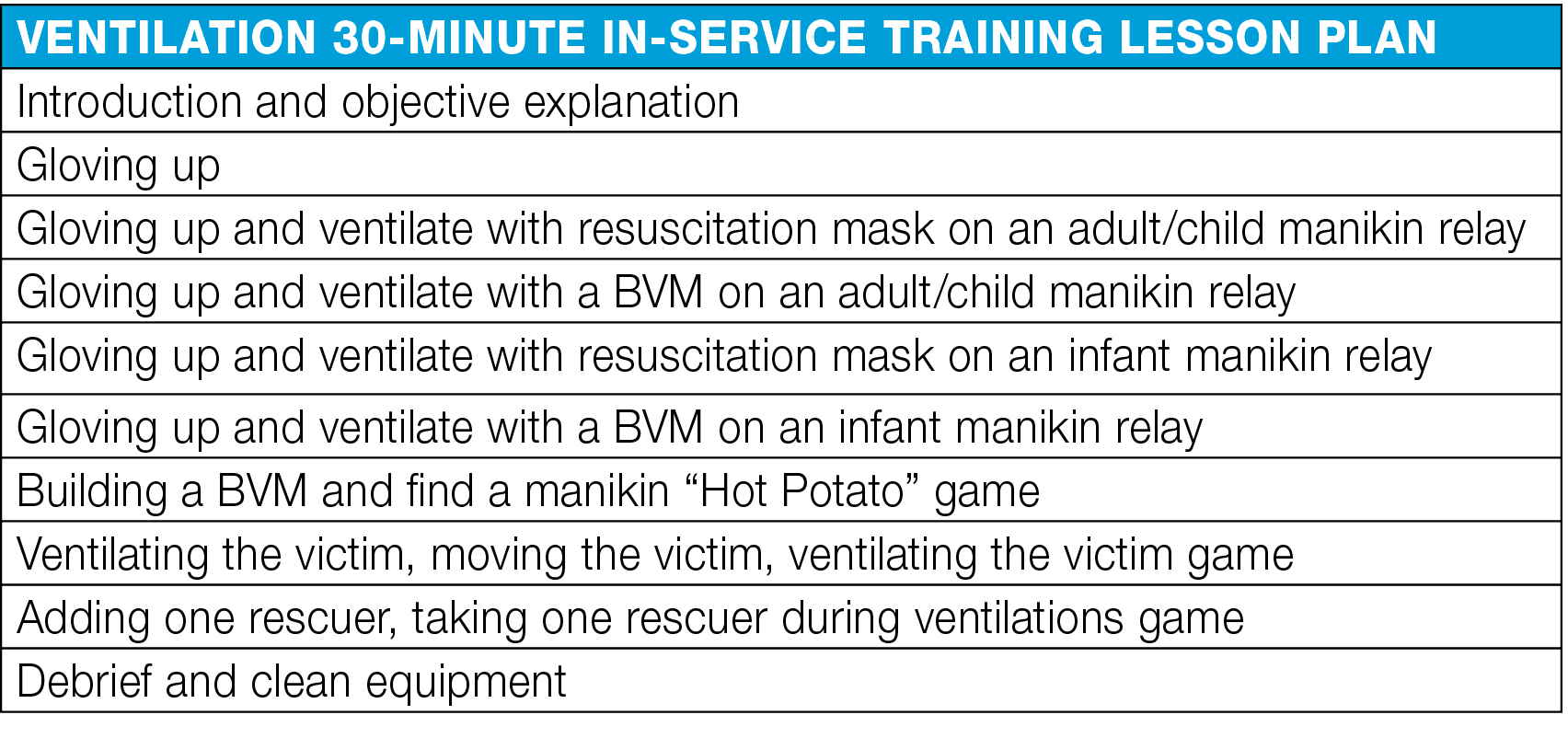

Below is an example of a 30-minute in-service training lesson plan, where each section of the table represents a 3-minute training block.

PREPARING AHEAD

It’s imperative that prepping all the equipment is completed before the in-service. Know what equipment you need and verify that it’s available, that it’s working properly (AED trainer) and there is plenty of it (gloves, rescue tubes, and spine board) for the staff that are coming to the in-service. Not doing this ahead of time, will eat into the in-service. You want your in-service training to run smoothly. This demonstrates to your staff that you respect and value their time and their time to train.

Besides prepping your equipment, review your own skill proficiency. If you are using additional staff as proctors, review their skill proficiency as well. Synchronize how you want the skills and objectives to be met, making sure everyone understands the results you’re looking for in the in-service. Make sure proctors can give feedback that moves the rescuer’s progression forward. Have proctors identify any rescuers that might need remediation for specific skills in the future.

FINAL THOUGHTS

You’re only as good as your last training. Being a great trainer requires an ongoing commitment to keeping your own skills at a high level of proficiency, both as a rescuer and a trainer. I firmly believe that you must be able to get into the water a nd do the same skills as your rescuers. If they are required to maintain a level of readiness through swim conditioning, you must do so as well. You don’t have to be the fastest or strongest, you just must be willing to get in the water like everyone else.

Good luck and keep training.